Refusing to Let Us Look Away

As a young reporter in Sarajevo, Janine di Giovanni remembers the fresh blood in the snow of young children. “They died because they went outside to play and got hit by a rocket.” In Sierra Leone, she held a six-month-old baby who had been amputated at the elbow by rebel soldiers as a way of terrifying civilians. In Kosovo and Syria, she spent months interviewing broken women who had been repeatedly raped, beaten and tortured. In Rwanda, she stayed in refugee camps where people fell at her feet, dying of cholera. For 25 years, she has reported the most horrific torture and human rights abuse in Palestine, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Somalia, Rwanda, Bosnia, Chechnya, Afghanistan, Iraq, and now Syria as well as many other places – she reckons more than 16 wars and conflicts. The worse day so far, she says, was when she watched a baby die in front of her in Aleppo, Syria, not from shelling or bombing – but from a common respiratory illness. The fighting in the streets was so bad that the parents could not get the baby to the hospital until it was too late. “I stood in a corner and cried and cried,” she says.

Janine and I met several years ago, at lunch in Greece, on a gentle afternoon with dear friends, as our young children played. A long, long way from any war zone.

Janine is the mother of a 12-year-old boy, Luca. When he was born in 2004, she taped a photograph of another little boy above her desk – that of Dili Babu, a three-year-old Indian child dying of AIDS. She wanted to always be reminded of the children who were not in Paris, not warm, not sheltered, not loved.

She is a fan of Christian Louboutin’s four-inch heels which she wears on book tours, she loves Roland Mouret dresses, but she doesn’t see a contradiction in this. In the field she wears flak jackets, helmets and hiking boots, but when she is home, she becomes an “Italian mama and an ordinary person. I walk my son to school. I go for a run in the Luxembourg, I go to Sephora and buy makeup. I get my nails done. I meet my girlfriends for lunches and cocktails. I see stupid movies. It’s the only way I stay sane.”

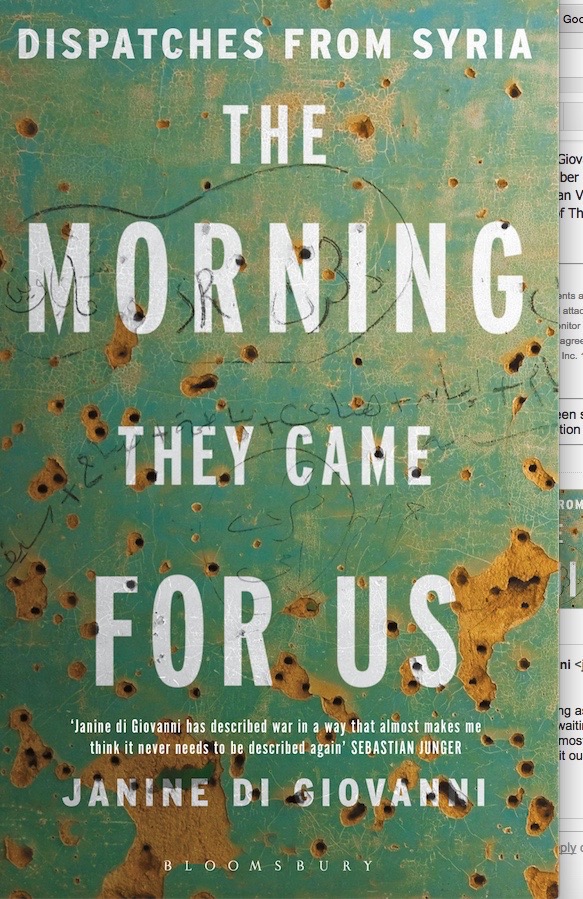

We talk on the eve that her book, The Morning They Came for Us, is launched in the US. It is a very short but emotionally rending read. Get it. It is important.

This book – and all the rest of her journalism – puts all 1st-world problems severely into perspective.

Her voice is assured but careful. You can hear the wisdom and the pain of experience in every sentence. “I feel so privileged that I can do this work – it makes me appreciate my life in Paris or London. Just being able to speak on the phone without someone listening in; having democracy; being able to eat fruit and vegetables. I am grateful for my son, my health, that I have food to eat at all. And everything else is just icing on the cake.”

The people to whom she gives a voice certainly have no cake – are completely dispossessed of all we deem essential.

But Janine is not without hope. She knows exactly what can make the difference, whether it’s giving people a voice or reading about these people or simply looking inside ourselves for our inner strength. She believes most deeply that “We can all bounce back. Any and every woman, whether a refugee or a comfortably-off mother, has resilience. It’s just a case of finding it. And targeting it. And developing it. We just have to listen to our little voice – we have huge strength of character.”

And she has witnessed this first-hand time and time again. “Recently I met refugee women who have had to leave their country. They are alone with their children for the first time in their lives. They have come from a society where men – fathers, husbands, village communities – had always made their decisions for them. Now they are in a country where they know they are not wanted, where they don’t speak the language, don’t know how to ask for medical care or how to find education for their children. And they are preyed on sexually: they are an easy target in the camps.”

“Can you imagine?”

I can’t.

And I still can’t imagine how she finds the strength to do her job.“How,” I ask,“do you leave your son?” The question hits a raw nerve, “I miss him, and he misses me.” She pauses. “But I have rules,” she continues, stronger again. “I never go for more than a week. I keep in touch with him all the time. I talk to him very carefully before I go. It’s just a different level of balance. Every woman in the world who works has to do a juggling act – whether it’s with danger or just prioritizing time. And I do prioritize him. If he said ‘I don’t want you to do this any more,’ then I would have to stop….” There is now a longer pause.

“But it is also what I do, and what I do well,” she resumes. “One of the great things about growing up is working out what you do well, what you are good at – just in the same way that it took me years to work out that Levi 501s don’t look good on me.”

We laugh. She is good at that too.

And then she adds, “You know, we should always keep something of ourselves that has nothing to do with our kids, our husbands or our homes –something that is really only ours. For me that’s work but it doesn’t have to be that. However, I really do believe that it is important to be economically independent of any man. When I split up from my first husband when I was 27, I said to a girlfriend ‘Oh but now I wont be able to buy pretty things,’ and she gave me a wake up call. ‘But now you can buy them for yourself’ – and that is so much better.”

Of course for me these words particularly mean so much.

Read more about this fascinating woman by clicking the attached links. And, go buy her book.

Twitter: @janinedigi

www.janinedigiovanni.com

New York Times Book Review

The Morning They Came For Us

Such a lovely women, how would we know about the trauma’s of the world, if there where not women such as she, with the ability to go into these place’s and report what she see’s. A true healer.

xo

Melissa

WOW!!!!! Mother Teresa would loved her… OX, Lizanne